Why extraterrestrial intelligence is more likely to be artificial than biological

November 28, 2021

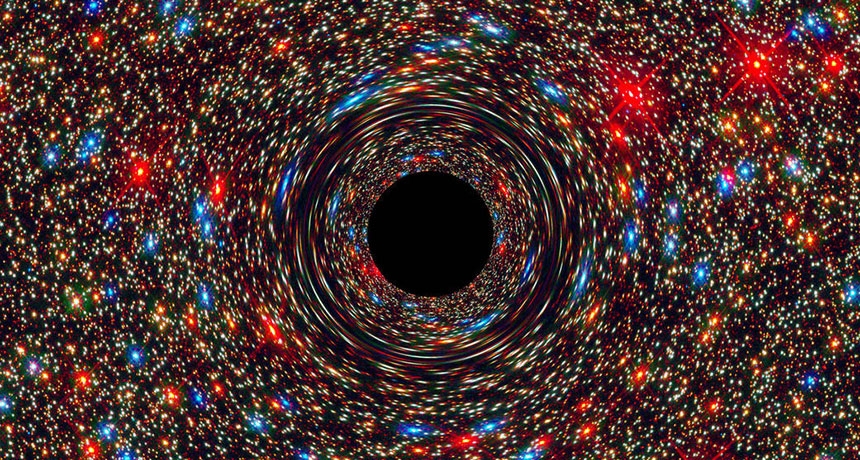

Whether extraterrestrial life exists or whether intelligent extraterrestrial life exists aren't the same question. Finding the former is, of course, more likely than finding the latter. We are simultaneously looking for both, but both require an entirely different approach.

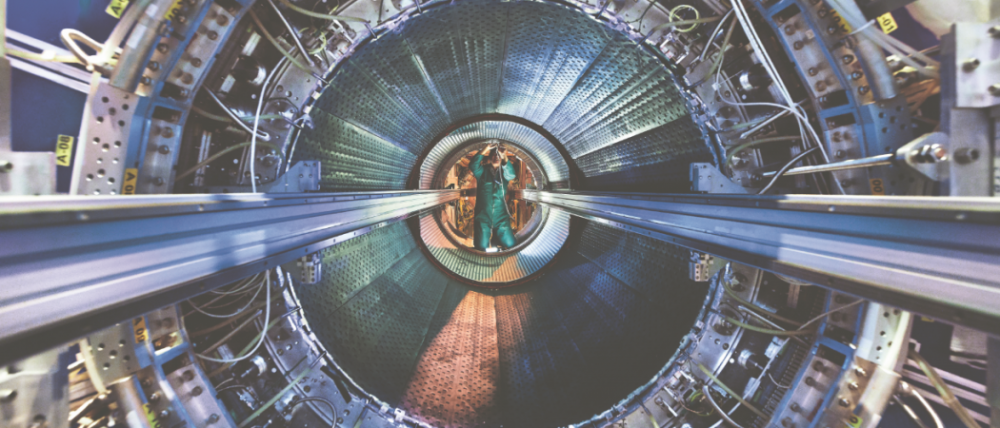

When it comes to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, SETI (which literally stands for Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence) contains a comprehensive variety of efforts.

During the early beginnings in the late 1800s, we first started looking for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence within our own solar system. In modern times, however, most of the global effort goes to monitoring electromagnetic radiation to detect potential transmissions.

A more recent niche avenue in the search takes aim at technosignatures (where scientists look for signs of megastructures like space mirrors and Dyson spheres). At the very cutting edge in the search, we find interstellar quantum communications. Scientists have only recently started thinking of concrete ways of how to search for this kind of transmission.

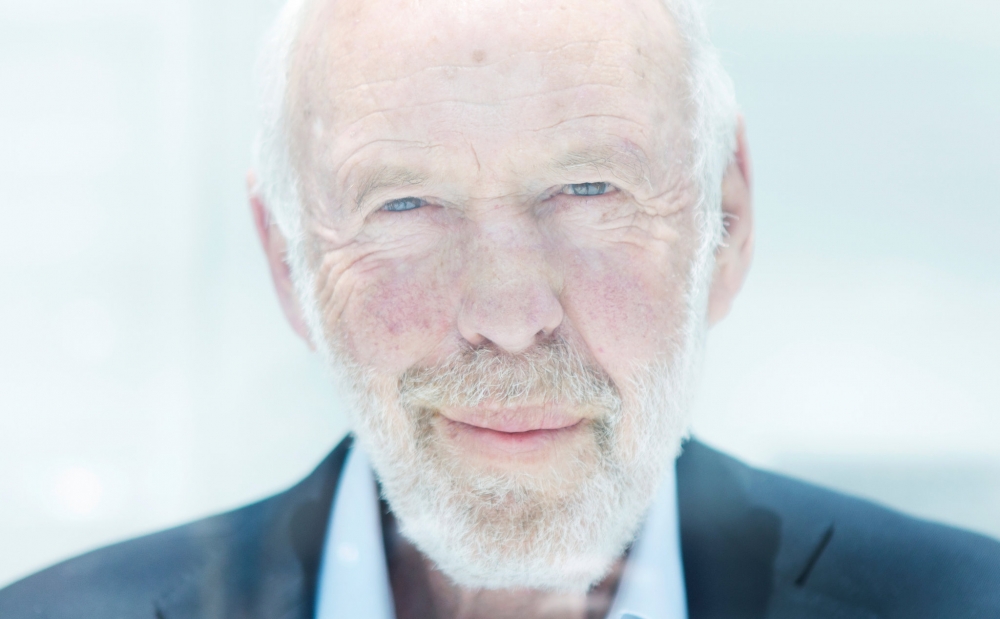

But if we are to actually discover extraterrestrial life, what do scientists expect to find? According to cosmologist Martin Rees, we aren't likely to find the classic aliens as commonly portrayed in sci-fi movies; he thinks it is far likely that we will stumble upon something else.

In this article, Rees explains why he expects that the bulk of civilizations out there would probably be artificial. Enjoy!

By Martin Rees - Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics, University of Cambridge