Dark Matter Still at Large

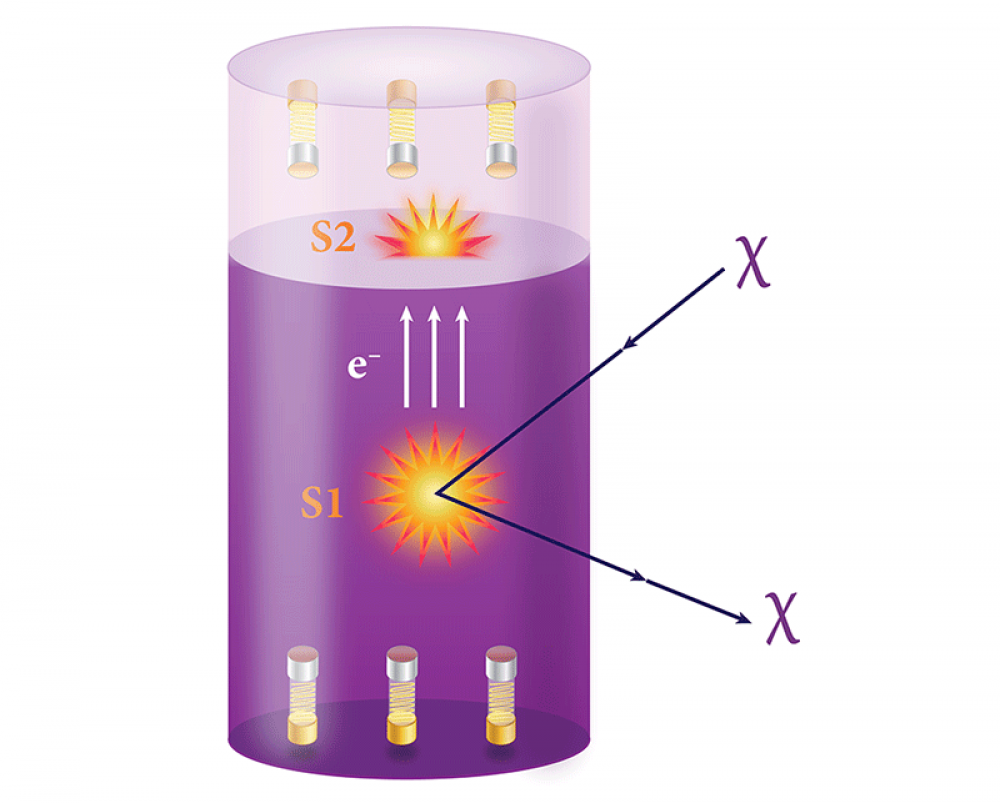

Figure 1: Both the LUX and PandaX-II experiments look for dark matter particles (𝜒) by sensing their interaction with xenon atoms. The detector in each experiment consists of a large tank of ultrapure liquid xenon (dark purple) topped with xenon gas (light purple). An interaction produces two light signals, one from photons, S1, and another, S2, from electrons when they drift into the gas. The signals are detected by photomultiplier tubes at the top and bottom of the tank (yellow cylinders).

Jodi A. Cooley, Department of Physics, Southern Methodist University, 3215 Daniel Ave., Dallas, TX 75205, USA

January 11, 2017• Physics 10, 3

No dark matter particles have been observed by two of the world’s most sensitive direct-detection experiments, casting doubt on a favored dark matter model.

Over 80 years ago astronomers and astrophysicists began to inventory the amount of matter in the Universe. In doing so, they stumbled into an incredible discovery: the motion of stars within galaxies, and of galaxies within galaxy clusters, could not be explained by the gravitational tug of visible matter alone [1]. So to rectify the situation, they suggested the presence of a large amount of invisible, or “dark,” matter. We now know that dark matter makes up 84% of the matter in the Universe [2], but its composition—the type of particle or particles it’s made from—remains a mystery. Researchers have pursued a myriad of theoretical candidates, but none of these “suspects” have been apprehended. The lack of detection has helped better define the parameters, such as masses and interaction strengths, that could characterize the particles. For the most compelling dark matter candidate, WIMPs, the viable parameter space has recently become smaller with the announcement in September 2016 by the PandaX-II Collaboration [3] and now by the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) Collaboration [4] that a search for the particles has come up empty.

See full text