Neutrinos Suggest Solution to Mystery of Universe’s Existence

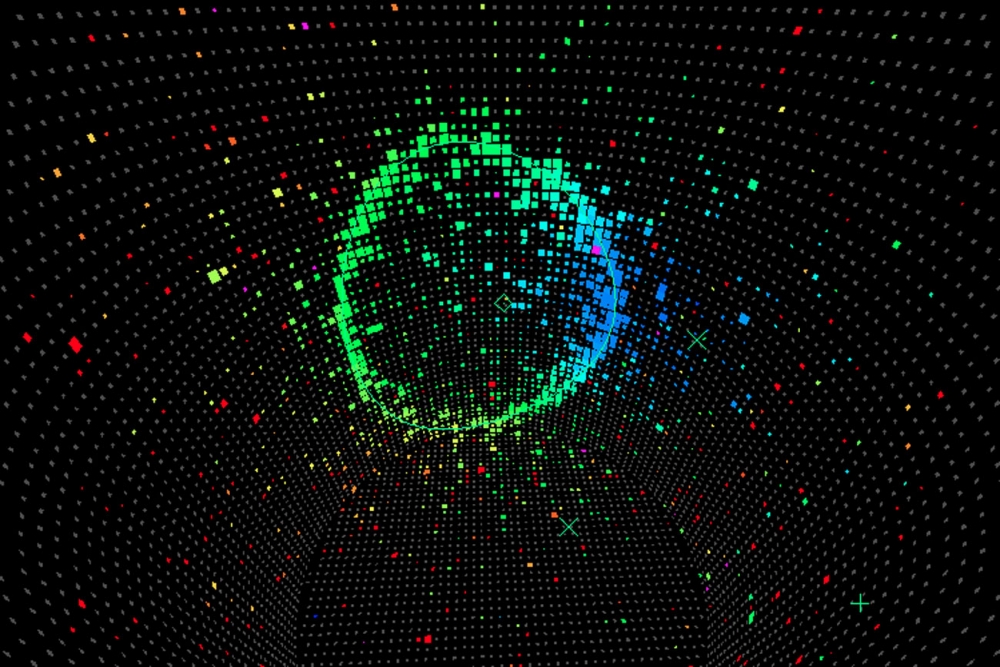

A neutrino passing through the Super-Kamiokande experiment creates a telltale light pattern on the detector walls.

Katia Moskvitch -- December 12, 2017

Updated results from a Japanese neutrino experiment continue to reveal an inconsistency in the way that matter and antimatter behave

From above, you might mistake the hole in the ground for a gigantic elevator shaft. Instead, it leads to an experiment that might reveal why matter didn’t disappear in a puff of radiation shortly after the Big Bang.

I’m at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex, or J-PARC — a remote and well-guarded government facility in Tokai, about an hour’s train ride north of Tokyo. The experiment here, called T2K (for Tokai-to-Kamioka) produces a beam of the subatomic particles called neutrinos. The beam travels through 295 kilometers of rock to the Super-Kamiokande (Super-K) detector, a gigantic pit buried 1 kilometer underground and filled with 50,000 tons (about 13 million gallons) of ultrapure water. During the journey, some of the neutrinos will morph from one “flavor” into another.

In this ongoing experiment, the first results of which were reported last year, scientists at T2K are studying the way these neutrinos flip in an effort to explain the predominance of matter over antimatter in the universe. During my visit, physicists explained to me that an additional year’s worth of data was in, and that the results are encouraging.

See full text