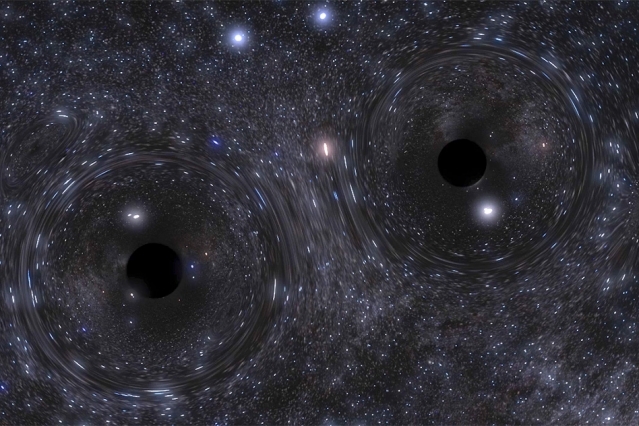

Dense stellar clusters may foster black hole megamergers

Black holes in these environments could combine repeatedly to form objects bigger than anything a single star could produce.

Jennifer Chu | MIT News Office

April 10, 2018

When LIGO’s twin detectors first picked up faint wobbles in their respective, identical mirrors, the signal didn’t just provide first direct detection of gravitational waves — it also confirmed the existence of stellar binary black holes, which gave rise to the signal in the first place.

Stellar binary black holes are formed when two black holes, created out of the remnants of massive stars, begin to orbit each other. Eventually, the black holes merge in a spectacular collision that, according to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, should release a huge amount of energy in the form of gravitational waves.

See full text