Five Surprising Truths About Black Holes From LIGO

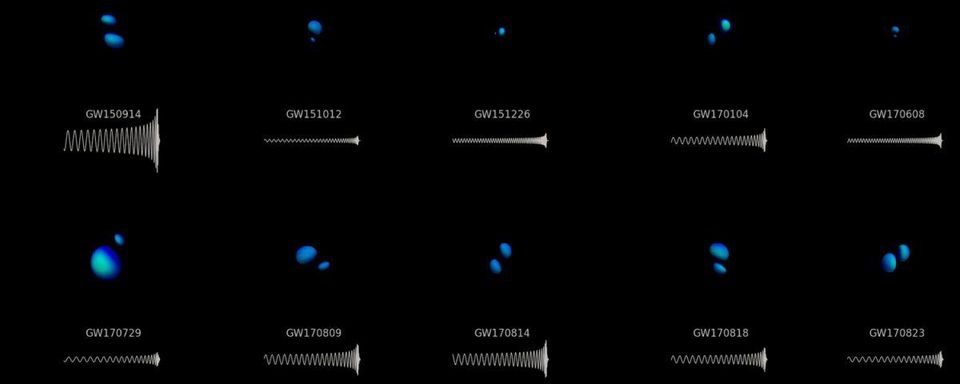

A still image of a visualization of the merging black holes that LIGO and Virgo have observed so far. As the horizons of the black holes spiral together and merge, the emitted gravitational waves become louder (larger amplitude) and higher pitched (higher in frequency). The black holes that merge range from 7.6 solar masses up to 50.6 solar masses, with about 5% of the total mass lost during each merger.TERESITA RAMIREZ/GEOFFREY LOVELACE/SXS COLLABORATION/LIGO-VIRGO COLLABORATION

Dec 4, 2018,

Ethan Siegel Senior Contributor

Science

On September 14th, 2015, just days after LIGO first turned on at its new-and-improved sensitivity, a gravitational wave passed through Earth. Like the billions of similar waves that had passed through Earth over the course of its history, this one was generated by an inspiral, merger, and collision of two massive, ultra-distant objects from far beyond our own galaxy. From over a billion light years away, two massive black holes had coalesced, and the signal — moving at the speed of light — finally reached Earth.

But this time, we were ready. The twin LIGO detectors saw their arms expand-and-contract by a subatomic amount, but that was enough for the laser light to shift and produce a telltale change in an interference pattern. For the first time, we had detected a gravitational wave. Three years later, we've detected 11 of them, with 10 coming from black holes. Here's what we've learned.

There have been two "runs" of LIGO data: a first one from September 12, 2015 to January 19, 2016 and then a second one, at somewhat improved sensitivity, from November 30, 2016 to August 25, 2017. That latter run was, partway through, joined by the VIRGO detector in Italy, which added not only a third detector, but significantly improved our ability to pinpoint the location of where these gravitational waves occurred. LIGO is currently shut down right now, as it's undergoing upgrades that will make it even more sensitive, as it prepares to begin a new data-taking observing run in the spring of 2019.