A Radio Flare from Colliding Stars?

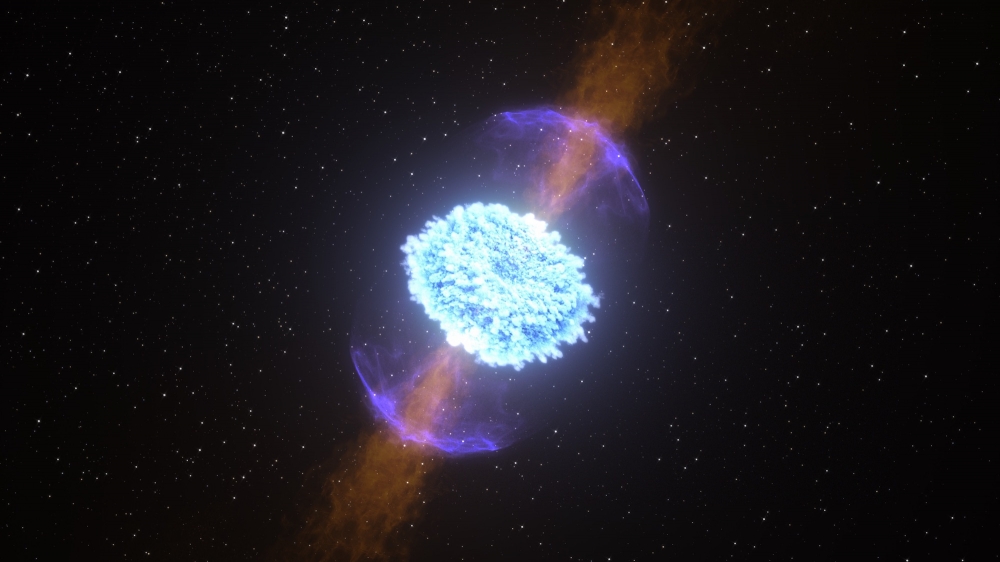

When neutron stars collide, the shell of expanding ejecta can interact with the surrounding interstellar medium, producing long-lived radio flaring. [NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/CI Lab]

By Susanna Kohler on 11 December 2020

When a pair of neutron stars collide, they emit a fireworks show. Could some of the low-energy light produced in these mergers be detectable years later? A team of scientists thinks so — and they’re pretty sure they’ve found an example.

A Rainbow of Signals

In addition to gravitational waves, a slew of electromagnetic radiation is produced in the merger of two neutron stars, spanning the spectrum from gamma rays to radio waves.

In 2017, the now-famous neutron star collision GW170817 gave us a first look at this expected emission: it revealed a short gamma-ray burst, infrared and optical light from ejecta in a kilonova, and relatively short-lived X-ray and radio afterglows caused by high-speed outflows.

But there’s one expected type of emission that was missing from GW170817, and it’s never before been spotted in any neutron star collision: radio flaring.

See full text