January 1, 1925: The Day We Discovered the Universe

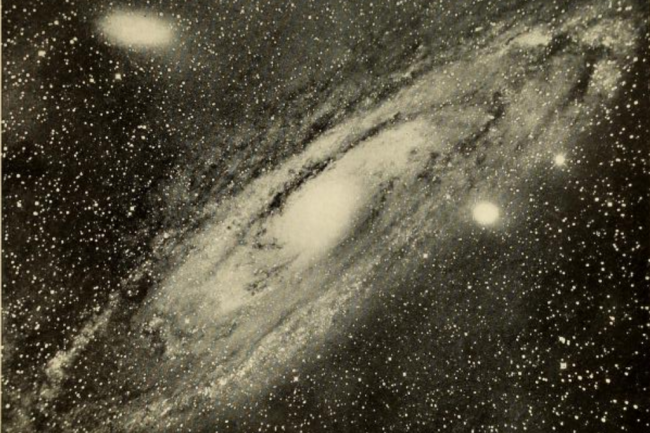

The Andromeda nebula, photographed at the Yerkes Observatory around 1900. To modern eyes, this object is clearly a galaxy. At the time, though, it was described as "a mass of glowing gas," its true identity unknown. (From the book Astronomy of To-Day, 1909)

Thanks to Edwin Hubble, we now can better comprehend the true scale of the universe.

By Corey S. Powell January 2, 2017

What’s in a date? Strictly speaking, New Year’s Day is just an arbitrary flip of the calendar, but it can also be a cathartic time of reflection and renewal. So it is with one of the most extraordinary dates in the history of science, January 1, 1925. You could describe it as a day when nothing remarkable happened, just the routine reading of a paper at a scientific conference. Or you could recognize it as the birthday of modern cosmology–the moment when humankind discovered the universe as it truly is.

Until then, astronomers had a myopic and blinkered view of reality. As happens so often to even the most brilliant minds, they could see great things but they could not comprehend what they were looking at. The crucial piece of evidence was staring them right in the face. All across the sky, observers had documented intriguing spiral nebulae, swirls of light that resembled ghostly pinwheels in space. The most famous one, the Andromeda nebula, was so prominent that it was easily visible to the naked eye on a dark night. The significance of those ubiquitous objects was a mystery, however.

See full text