Hubble Finds That the Nearest Quasar Is Powered by a Double Black Hole

ABOUT THIS IMAGE:

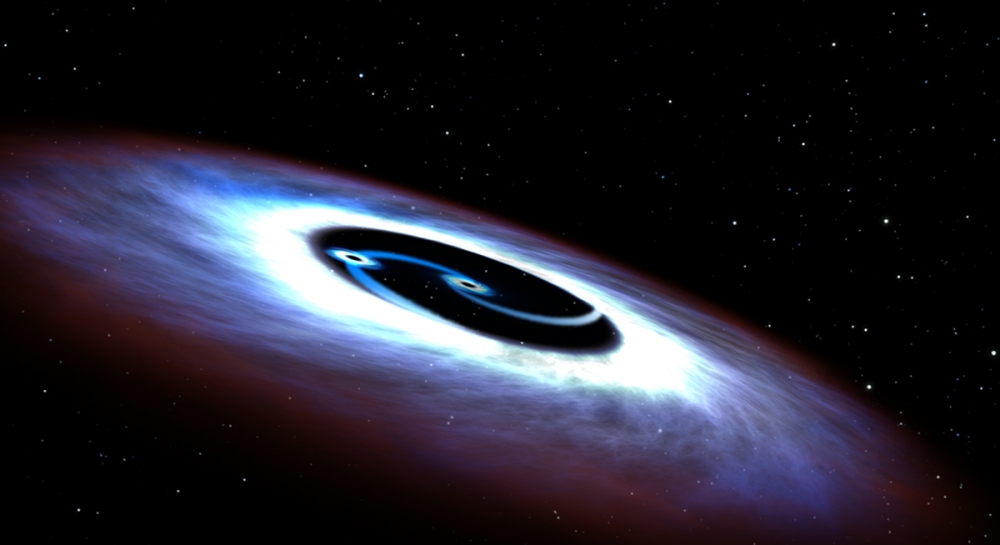

This artistic illustration is of a binary black hole found in the center of the nearest quasar host galaxy to Earth, Markarian 231. Like a pair of whirling skaters, the black-hole duo generates tremendous amounts of energy that makes the core of the host galaxy outshine the glow of the galaxy's population of billions of stars. Quasars have the most luminous cores of active galaxies and are often fueled by galaxy collisions.

Hubble observations of the ultraviolet light emitted from the nucleus of the galaxy were used to deduce the geometry of the disk, and astronomers were surprised to see light diminishing close to the central black hole. They deduced that a smaller companion black hole has cleared out a donut hole in the accretion disk, and the smaller black hole has its own mini-disk with an ultraviolet glow.

Astronomers using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have found that Markarian 231 (Mrk 231), the nearest galaxy to Earth that hosts a quasar, is powered by two central black holes furiously whirling about each other.

The finding suggests that quasars — the brilliant cores of active galaxies — may commonly host two central supermassive black holes that fall into orbit about one another as a result of the merger between two galaxies. Like a pair of whirling skaters, the black-hole duo generates tremendous amounts of energy that makes the core of the host galaxy outshine the glow of the galaxy's population of billions of stars, which scientists then identify as quasars.

Scientists looked at Hubble archival observations of ultraviolet radiation emitted from the center of Mrk 231 to discover what they describe as "extreme and surprising properties."

If only one black hole were present in the center of the quasar, the whole accretion disk made of surrounding hot gas would glow in ultraviolet rays. Instead, the ultraviolet glow of the dusty disk abruptly drops off towards the center. This provides observational evidence that the disk has a big donut hole encircling the central black hole. The best explanation for the observational data, based on dynamical models, is that the center of the disk is carved out by the action of two black holes orbiting each other. The second, smaller black hole orbits in the inner edge of the accretion disk, and has its own mini-disk with an ultraviolet glow.

See full text