What Are Quantum Gravity's Alternatives To String Theory?

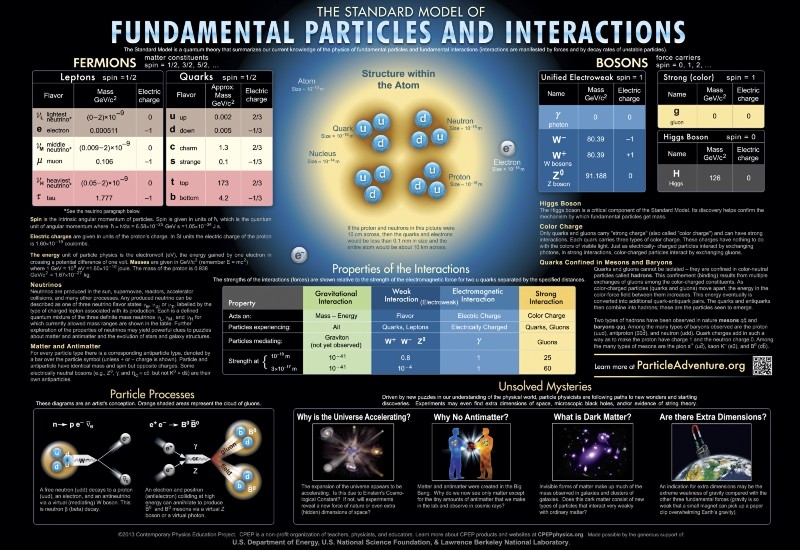

Image credit: CPEP (Contemporary Physics Education Project), NSF/DOE/LBNL.

The Universe we know and love — with Einstein’s General Relativity as our theory of gravity and quantum field theories of the other three forces — has a problem that we don’t often talk about: it’s incomplete, and we know it. Einstein’s theory on its own is just fine, describing how matter-and-energy relate to the curvature of space-and-time. Quantum field theories on their own are fine as well, describing how particles interact and experience forces. Normally, the quantum field theory calculations are done in flat space, where spacetime isn’t curved. We can do them in the curved space described by Einstein’s theory of gravity as well (although they’re harder — but not impossible — to do), which is known as semi-classical gravity. This is how we calculate things like Hawking radiation and black hole decay.

But even that semi-classical treatment is only valid near and outside the black hole’s event horizon, not at the location where gravity is truly at its strongest: at the singularities (or the mathematically nonsensical predictions) theorized to be at the center. There are multiple physical instances where we need a quantum theory of gravity, all having to do with strong gravitational physics on the smallest of scales: at tiny, quantum distances. Important questions, such as:

What happens to the gravitational field of an electron when it passes through a double slit?

What happens to the information of the particles that form a black hole, if the black hole’s eventual state is thermal radiation?

And what is the behavior of a gravitational field/force at and around a singularity?

See full text